Study finds racism—and resistance to it—beneath the surface in high school physics

Researchers at the University of Copenhagen wanted to understand how high school students interacted with a physics learning game. However, the observations contained so many examples of problematic behavior that it couldn't be overlooked.

Casual racism

Jesper Bruun brought his many hours of classroom recordings to KT Doerr, who was working on the Marsbase project at the time and is now an assistant professor at Malmö University, researching the intersection of gender and science education. Together, they selected groups of students whose conversations were analyzed in detail.

KT Doerr expected to hear students discussing their own ethnicity and gender, as they are young people developing their identities. Still, KT was surprised by what the students said during physics class.

“When I first saw the transcriptions of these conversations, I had a hard time believing it,” says KT Doerr.

One of the high school classes was predominantly made up of ethnic Danes. Much of the classroom conversation was racially charged, KT Doerr explains.

“For example, there’s a group that identifies as Group K, and we can hear someone in the background saying ‘Ku Klux Klan.’ This kind of talk happens when students walk in or chat during breaks. And we don't see the teacher reacting to it,” says KT Doerr.

Research Through Comics

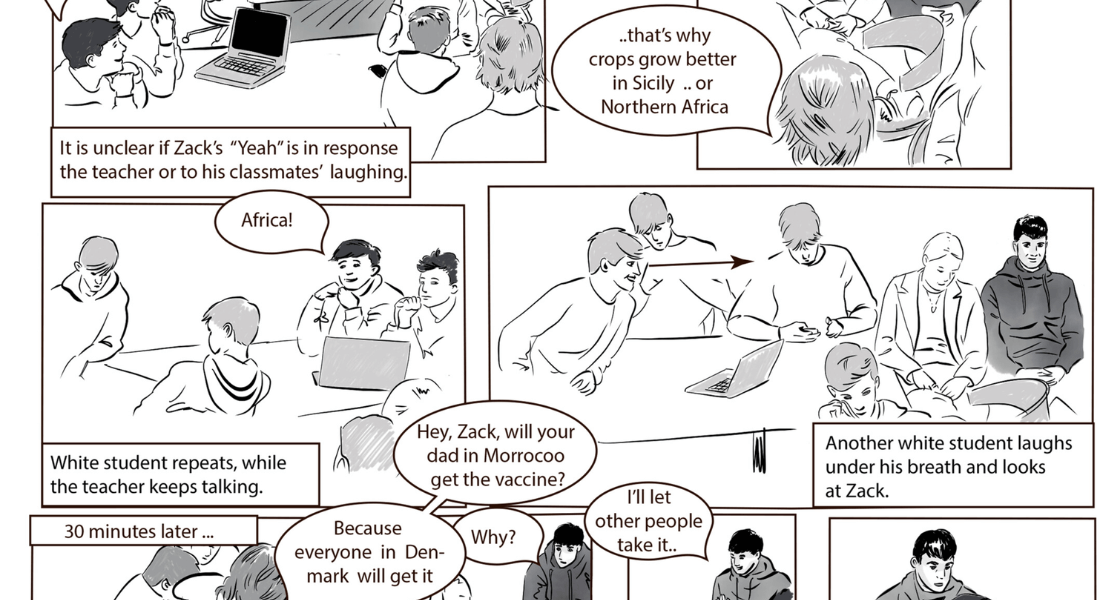

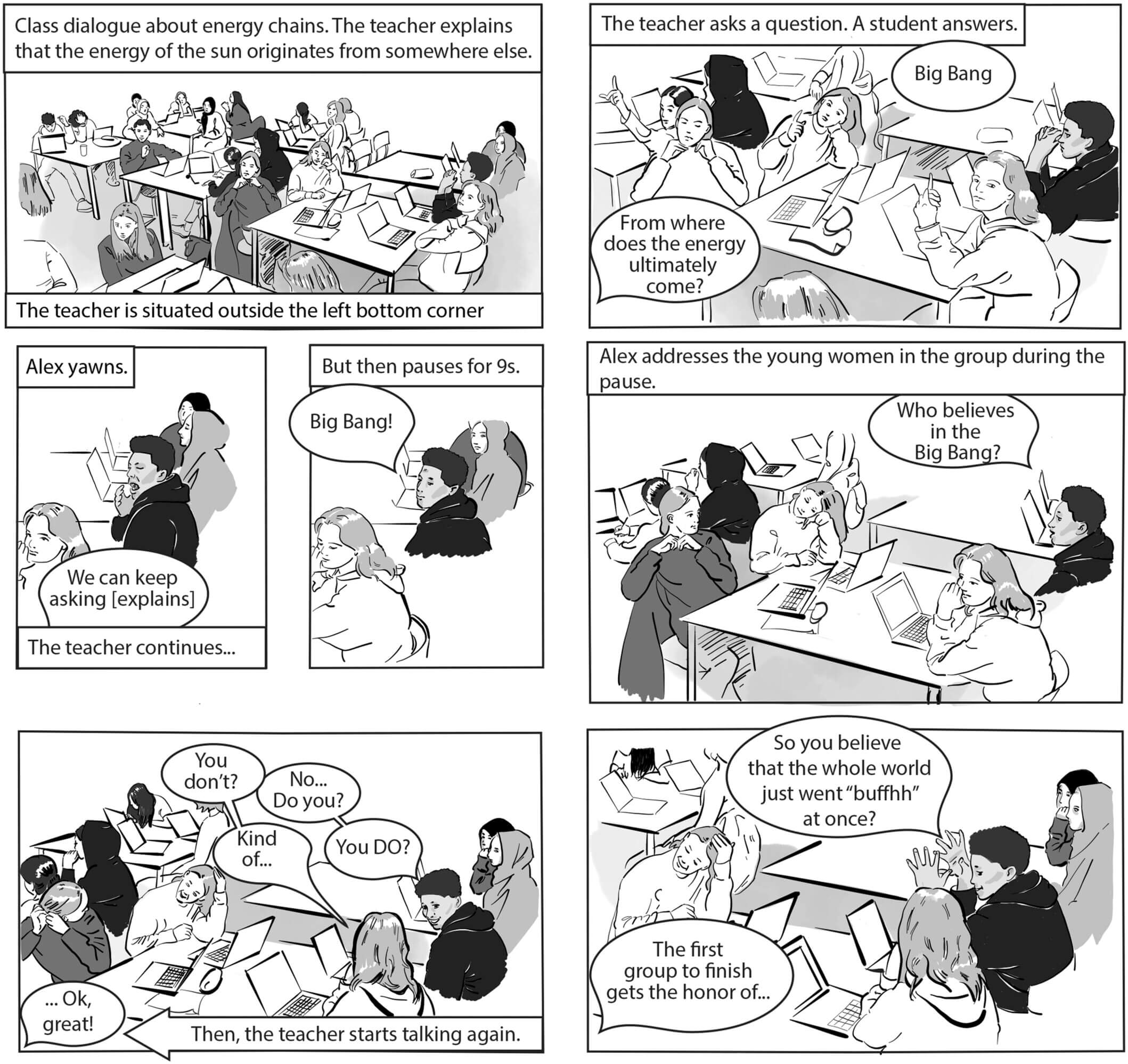

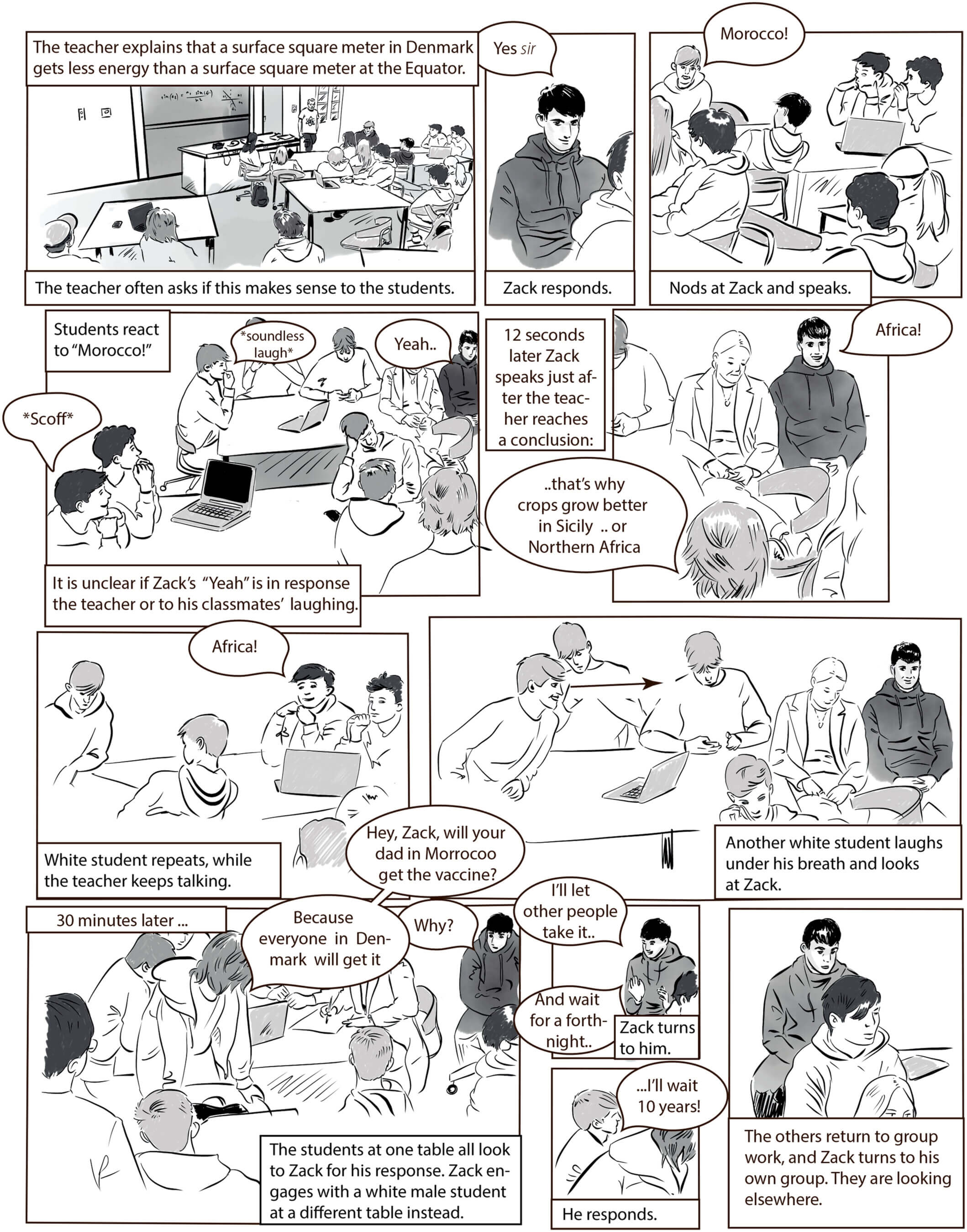

In the new study, Jesper Bruun and KT Doerr use comic strips to depict the situations they observed in the classrooms. Bruun believes the format provides a better understanding of what really transpired between the students.

“Instead of just reading the words that were said, we can illustrate with the comics what’s going on with the students’ body language and so on. That would be very difficult to describe in text,” he says.

The two researchers selected sequences of frames from the video observations, which, through illustrator Sanne Harder, were turned into comic panels. The result is three comics chosen to showcase different types of interactions.

A pattern that need to be broken

KT Doerr coded every comment made by the selected student groups to determine when they talked about physics and when they discussed other topics.

In one group, 520 statements were categorized, of which 99 were overtly sexist remarks.

Other observations were more subtle, such as when students automatically assumed that astronauts were men, or when students of different ethnic backgrounds were made to represent everything happening south of the border.

“This is problematic, and it’s important that physics education is capable of breaking these patterns,” says KT Doerr.

If we want to make physics education—and science education in general—more inclusive for different ethnicities and genders, we have to address this.

On the other hand, the researchers also saw instances where students supported each other in expressing their different experiences and languages as part of learning physics.

“When we see students discussing speaking Arabic on Mars, the implication is that they’re not allowed to do that on Earth. So in that way, we also see students resisting the underlying racist tone,” says KT Doerr.

“We believe it’s important to bring these issues to light so that teachers can ultimately address the negative aspects and support the positive ones.”

Cannot be isolated

For some teachers, this might feel like a challenge they’re not equipped to handle. But it’s necessary, says Jesper Bruun.

“If we want to make physics education—and science education in general—more inclusive for different ethnicities and genders, we have to address this.”

When studying how high school students learn physics, you cannot isolate it to just their academic discussions, Jesper Bruun emphasizes. Learning is intertwined with everything else that happens in the classroom.

“You’re not just learning about energy or electricity. There are affective factors that come into play,” says Jesper Bruun.

“So, if there’s overt racism or sexism in the space where you learn physics, and you start to view the physics class as a place where you not only learn physics but also learn to be sexist and racist, then that’s a problem.”